What is True in the Cabrini Movie?

What is True in Cabrini?

By Rod Barr, Screenwriter of Cabrini

WARNING: This article contains spoilers!!

Orphans at West Park

The Writing Process

Many folks who’ve seen CABRINI want to understand how we balanced the historical record with the art and craft of filmmaking. It’s a fascinating and complex question.

I should begin by saying that we had no interest in making a documentary-style movie of Cabrini’s life, with a strict adherence to factual accuracy. Our goal was to make a beautiful dramatic movie that captured the essence of Cabrini the person – the truth of her heart and soul. This necessarily required creative license.

In my opinion, a good biopic is closer to poetry than it is to a book of history. Movies use the language of images and dialog, the power of music and lighting and acting, to communicate a deeper and more immediate human truth than straight history could ever express.

That said, my writing process began with months and months of factual historical research. I read innumerable books and articles on Mother Cabrini – anything I could lay my hands on. (If you’re interested in reading more about Cabrini from a historical perspective, I list a few of the most useful books in a brief bibliography at the end of this page.)

Executive Producer Eustace Wolfington and I also visited all of Mother Cabrini’s main sites in Italy, walked in her footsteps, and conducted lengthy interviews with historians of her Order.

Executive Producer Eustace Wolfington and Screenwriter Rod Barr in Italy

Out of these travels and discussions emerged a few essential insights – and even specific scenes – without which the movie would not be what it is.

Every single moment of the movie – whether invented or factual – was informed by historical research. Here are just a few prominent examples, from among many I could have chosen:

Cabrini in Italy

The main action of the movie begins when Cabrini visits Pope Leo XIII at the Vatican and gets his permission to begin an overseas mission.

Pope Leo XIII

Though we compressed a number of actual meetings into one dramatic movie scene, the essence of the Vatican sequence is historically accurate:

The male leadership of the Church did not believe that Mother Cabrini (or any woman, for that matter) could lead an overseas mission without the oversight of men. It was considered too difficult and too dangerous for women.

Pope Leo XIII, however, sensed Cabrini’s genius and ambition – and was willing to take a chance… but only if Cabrini gave up her dream to lead a mission to China, and instead served Italian immigrants in New York.

In the movie, the Pope says: “Go West, not East.” This is a direct quote from the historical record.

Only a few bits of actual dialogue survive in the historical record, and among them is this exchange from the Vatican scene: Cardinal: “There has never been an independent Order of missionary women!” Cabrini: “Mary Magdalen brought news of the Resurrection to the Apostles. If the Lord confided that mission to a woman, why should he not confide in us?!”

Five Points

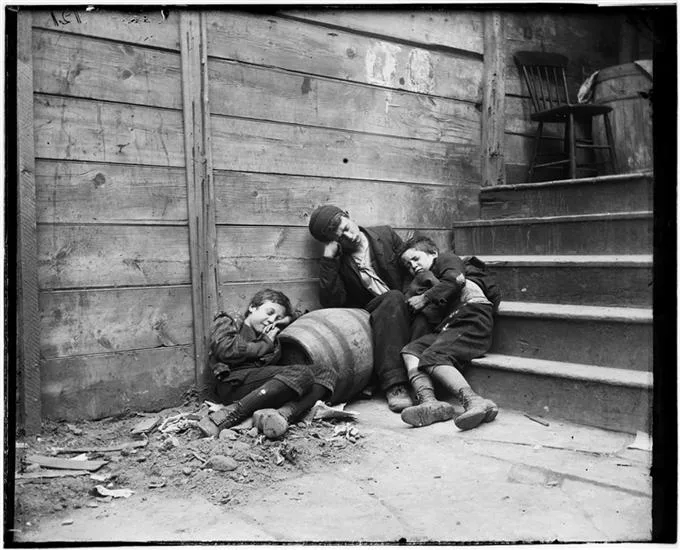

Cabrini spent her first night in America in the Five Points section of New York, a desperate, often violent slum in lower Manhattan. The movie’s portrayal of Five Points can at first seem like an exaggeration, but I promise: our production designer, Carlos Lagunas, based the sets on actual historical photographs. Five Points really was that bad – and probably worse.

Most of the information about life in Five Points comes to us through the astonishing photographs of Jacob Riis, who documented life in the slums with brutal accuracy.

These are among the many Riis photos that designers used to create our sets.

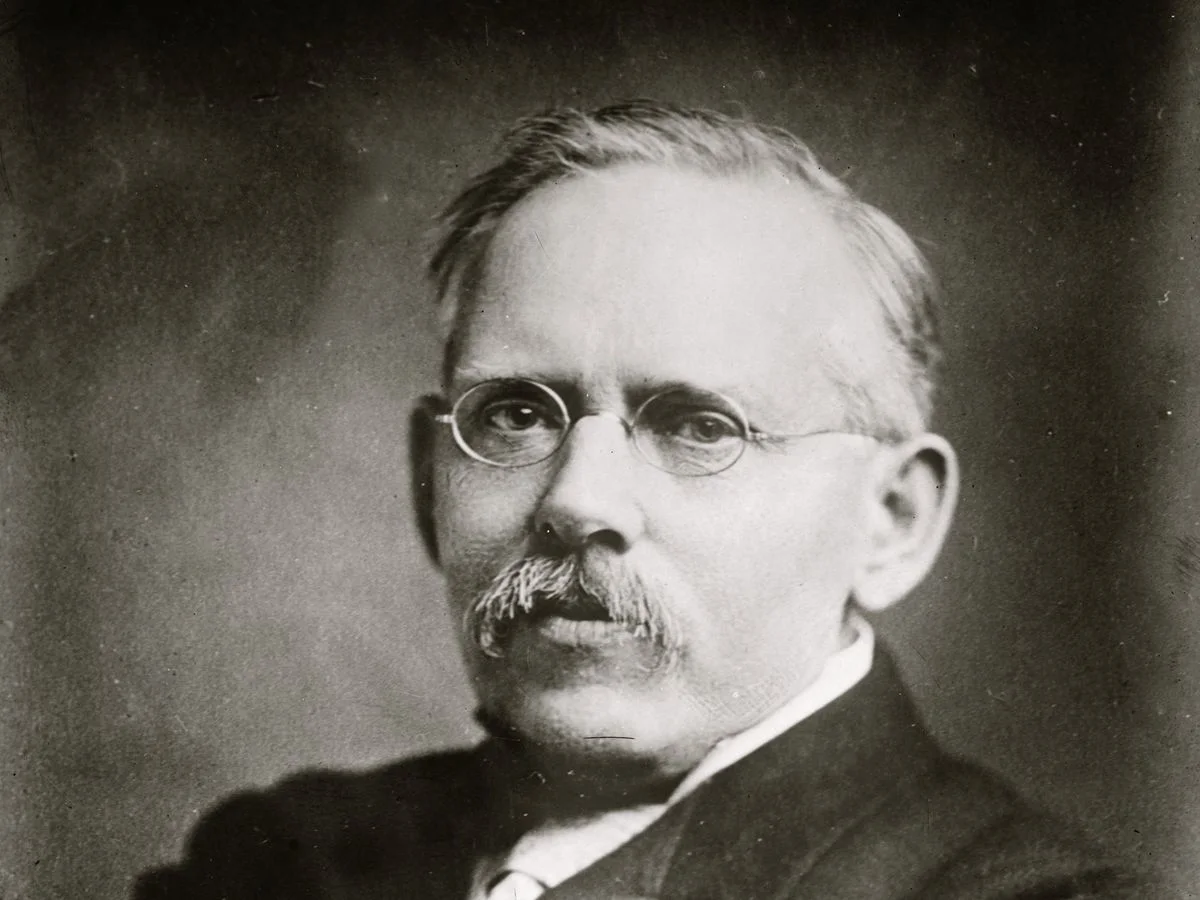

Jacob Riis

Check out the photograph by Jacob Riis of three little homeless boys sleeping in a stairway. In an homage to Riis, director Alejandro Monteverde reproduced this exact image in a shot from the movie! Look for it when you go and see Cabrini a second time.

Homeless Boys in Stairway, Photographed by Jacob Riis

Archbishop Michael Corrigan

The day after she arrives in America, Cabrini has a key encounter with Archbishop Corrigan, played by the wonderful David Morse. The Archbishop essentially tells her to get on a boat and go back to Italy. Historically, this encounter happened in much the way the movie presents it.

Corrigan was a complicated man. He was a good priest who nevertheless gave preference to the interests of Irish Catholics – his countrymen – over the interests of freshly arrived Italian Catholics.

Corrigan did indeed forbid Cabrini from soliciting money from Americans. This made it difficult – if not impossible – for Cabrini to fund her mission. But Cabrini always found a way to protect her children, no matter what obstacles stood before her.

The Underwater Scenes

The shots of young Cabrini underwater are abstract and imagistic – but they are nonetheless grounded in historical truth.

As a young girl, Cabrini did in fact fall into a fast river while playing with paper boats, and almost drowned. We took that historical reality and used it to chart the inner life of the character, using underwater images to present her psychological state in moments of stress.

Here’s a photo that I took of the actual place near Sant’Angelo where Cabrini fell into the river.

Where Young Cabrini Fell Into the River

Cabrini's Orphanage on the Hudson

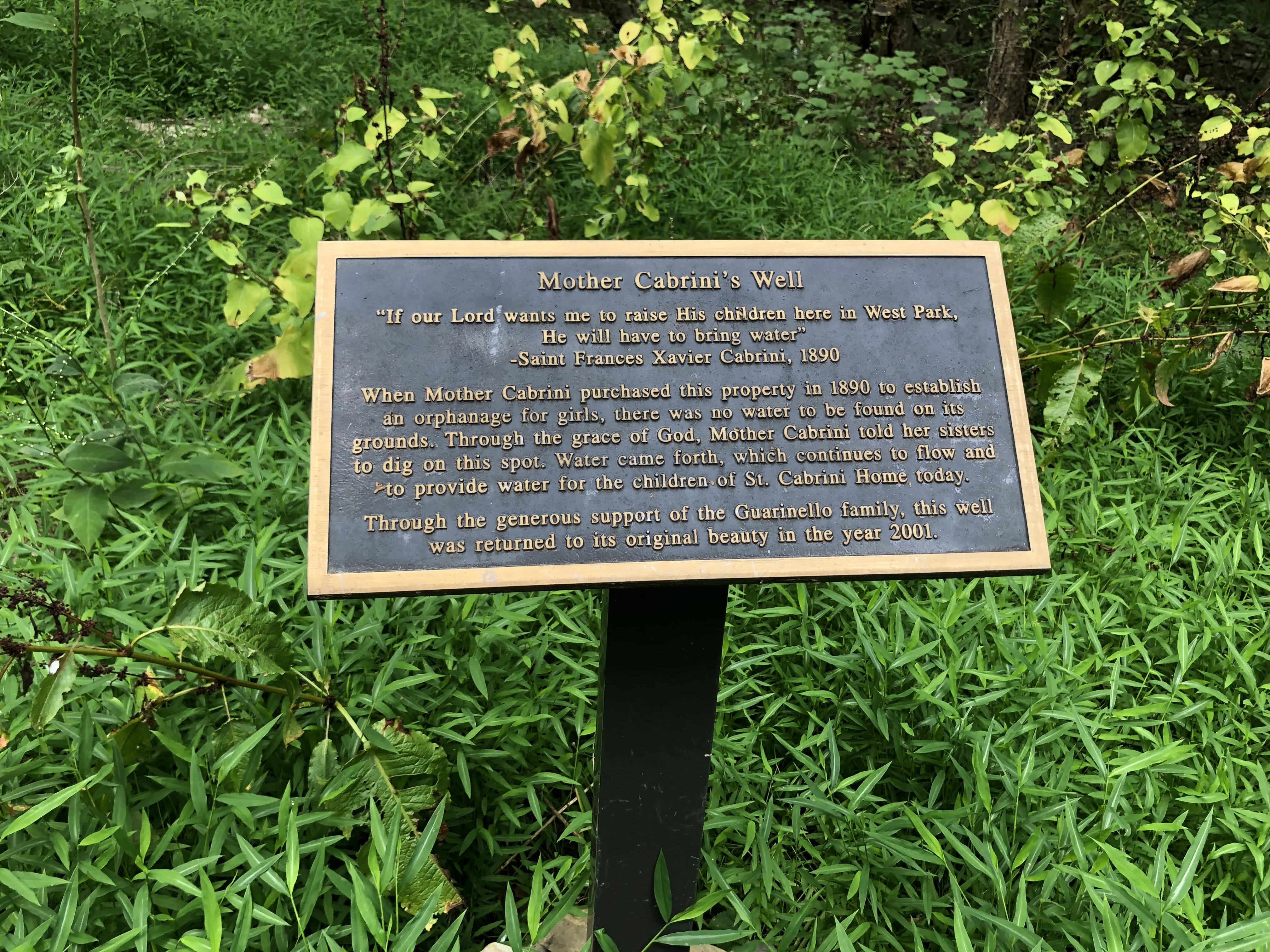

When Cabrini established an Italian orphanage in the nice part of Manhattan – not far, in fact, from Archbishop Corrigan’s church – Corrigan looked for a way to get her out. So he offered her an abandoned, worthless Jesuit seminary with no water.

Its name was West Park.

Orphanage on the Hudson (West Park)

Cabrini accepted his offer, found water on the property – and turned West Park into one of the most valuable properties in her whole portfolio.

When my wife and I traveled to West Park for research, we found this plaque at the site where Cabrini found water.

Plaque at Well at West Park

The Scene at the Italian Senate

In one of the key scenes of the movie, Cabrini storms into the Italian Senate, uninvited, and proceeds to give a fiery speech that changes the minds of the Senators – and transforms the destiny of her mission.

Cabrini in the Senate

The movie’s depiction of the scene is essentially true, but – astonishingly – the moment appears in none of the books written about Cabrini.

I first heard about the scene during our research trip to Italy, in a casual comment by one of the historians of the Order, who said: “Then of course there was the time she stormed into the Senate!”

Amazed, I dug for more information – and discovered an amazing scene, passed along from nun to nun, that would become essential to the arc of the movie.

Why Doesn't the Senate Scene Appear in any History Books?

I asked myself that question, too – and here’s my take. Most history books about Cabrini are based in large part on a biography called “Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini,” by Mother Saverio de Maria. The book was published in 1927, ten years after Mother Cabrini’s death.

That book, I believe, was written largely to promote Cabrini’s chances of becoming an official saint. In other words, I believe the book was whitewashed, stripped of any scenes that Vatican officials might find objectionable or unbecoming of a saintly woman. If Cabrini ever seemed too aggressive, too certain of herself, too radical… that moment was written out of history.

And how much more radical and disruptive can you get than bursting uninvited into the Italian Senate and commanding the attention of men who believed that you, as a woman, had no right to be there?

More Questions Answered

As people see Cabrini in theaters, they often come out with an eagerness to know more about her. Here’s a quick rundown of some more things you may have been curious about.

Q: How old was Cabrini when she arrived in New York and what was her age throughout the film?

A: She arrived in New York at the age of 38. The movie covers a few years of her life, so I'd say it dramatizes her from age 38 to her early 40s.

Q: Do you have any more details about the plight of Italian immigrants?

A: It's difficult for us to conceive that Italians were called "brown-skinned animals" and were considered the lowest of the low. One immigrant wrote from New York: "Here we live like animals. We live and die without priests, without teachers, without doctors." Any good historical resources about Italian immigration will paint a similar picture of desperation. By the way, this is why I wrote that card at the beginning of the movie, which says something like: "Many Americas considered Italians to be of inferior intelligence... And a threat to the very fabric of America." Without stating this up front, as a plain fact, I was concerned that audiences wouldn't believe it.

Q: Was the newspaper article "Even Rats Have It Better" a real article?

A: That newspaper article was inspired by a real article that ran in a New York newspaper. The first lines of the article are directly quoted in the movie: "Over the last few months, a group of dark-eyed nuns..."

Q: What was Cabrini's relationship with Disalvo, the opera singer?

A: The opera singer, Disalvo, is a composite character, based mostly on people Cabrini met not in New York but in New Orleans. Part of the art and craft of screenwriting is to find ways to weave together elements that may have occurred in other places—and other times—into one unified story that captures a deeper truth. And in New Orleans, Cabrini used music—specifically Italian opera—to open the hearts of Americans to the Italians in their midst.

Q: What was Cabrini's relationship with Dr. Murphy?

A: Dr. Murphy is another composite character. He represents the many American doctors and businessmen (many of them Irish and Jewish) who helped Cabrini in her various enterprises. One of these many men was named Dr. Murphy.

Bibliography

If you want to get the fullest sense of Cabrini the person… watch the movie! If you’re interested in a deeper historical dive, I can recommend these books.

Too Small a World: The Life of Mother Cabrini by Theodore Maynard.

Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini by Mother Saverio de Maria.

Mother Cabrini: Italian Immigrant of the Century by Mary Louise Sullivan.